Year: 2020

Duration: 21 minutos.

Editing by: Rafael Menéndez

Music: Rossano Snel

“If you are coherent with yourself, the rest is bearable.

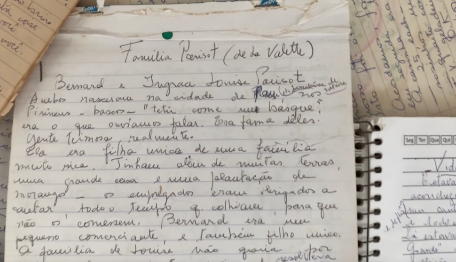

I bear,” Parisot quotes Brazilian poet Hilda Hilst, a literary and female icon. This is how she begins her second video, in the present day, in a quarantined Buenos Aires, in 2020. Conceived as a “visual journal of the pandemic,” Parisot features dizzying images, including flashbacks, a literary device that juxtaposes different times and thus builds a three-dimensional narrative.

“How did I get to this city? How did I get to this house?” She wonders, and it leads to a recap of her life, a form of catharsis: “I am telling a story because, as Isak Dinesen says, all sorrows can be born if you put them in words, in a story.”

With the TV show A crucigramista, Parisot trained herself in a really effective game of mixing words and images that is heir to the tradition of collage.

In the new video, she makes use of that experience and the logic behind the archive, the collection of images and texts that lay the foundation of a memory.

Parisot arrived in Buenos Aires in 2016. “Since I’ve been in this city, in this house, next to this fireplace, past, present and future are a single thing and they change, because the only thing that’s certain is that there is change,” she says. “Life is change: me, you, molecules, viruses, the planets, the stars, every being. Everything’s changing all the time.”

The drastic, unpredictable and unavoidable changes that the pandemic has brought about added up to the pattern that had actually ruled her life. Different relationships, countries, dreams were the norm for an existence that claims to feel “foreign everywhere.” The pandemic confirmed that she is designated by change, although the body refuses to transform itself so easily.”

In an existential tone, she asks herself: “What does it mean to be me today? What does it mean to be a mother? Are my words and my actions coherent? Is my inner reality in harmony with my external reality? I’m alive and my life is not fiction. I am not fiction. My body is not fiction. This voice is not fiction.

This is my voice. If I were a character, I could say whatever I wanted. But since the character in this story is the author, I am forced to censor myself so that I’m not taken to trial by those who I accuse or get offended.” Is art freedom?

On what conditions? In times like these when the social networks and vigilant technologies blur the lines between the public and the private, Parisot challenges us by showing this false freedom that is built on the spectacularization of private life. But we clearly cannot avoid how the “system” weighs on those who unabashedly challenge it.

“When I was between the ages of 7 and 13, (peeep!!!) molested me,” we hear and, despite the self-censorship, what is said is enough.

“Where’s my freedom of speech? Don’t I have the right to an autobiography? At the end of the day, don’t they say that every autobiography is autofiction?

Family, human relationships, nations, religions, governments, all permeated by censorship, by the unsaid. Is it better to keep quiet on the things we can’t talk about?” She reflects in disbelief.

“My only walk: to the supermarket,” she whispers while the Sex Pistols sing the anthem of anarchist punk (No future – No future – No future for you – No future – No future – No future for me). “Isolated but virtually connected to everyone, online, subdued to a techno-totalitarianism in which artificial intelligence consists of data capture, and feelings become the daily reality. Without touch, without skin, without being able to share the air we breathe, behind masks, locked up at home. Meanwhile, some ducks can walk across Libertador Avenue, a few blocks away from my house,” Parisot reflects.

The fallacies of the Anthropocene reveal its failure and the danger, which is no longer imminent but current. The echoes of a new humanism that questions the universe’s submission to human rule and law can be sensed in Parisot’s words.

“Apocalypse now, here.” “Danger a few meters away.

The mistake was believing the Earth is ours, truth is we belong to the Earth,” Nicanor Parra asserts with his unmistakable voice.

“The body is not fiction. The body is not virtual.

How are we going to perceive the body of another when it’s all over? Will we create a new consciousness that will allow us to have a friendlier relationship among humans and non-humans? Can anyone feel okay in this sick society? Will this be our chance to bet on collectiveness? Who decides how things are going to be from now on?”

“My mentor died, my first love died, the father of my children died. I am a woman, I am a mother, I am an artist, I share the bed and my life with my longest one night stand, and I finally understand that there are no guarantees or free lunches…”

“A new era begins: I am Paula Parisot,” the artist concludes in a self-referential gesture typical of the Literature of the self.

The mythicized “I” of the physical installation made up of grandparents, lovers, husband, children unveils itself through the reflection that the pandemic triggers. Nevertheless, Parisot makes up her autobiography, which is necessarily fictional, with traces of a personal archive that, like every archive, is selective and subject to a reading that recognizes it as such or simply dismisses it. “Who is afraid of the literature of the self?” Parisot seems to tell herself. Great poets have practiced it.

As Juan Sklar points out, “even Borges when he says, ‘a woman hurts me in all my body’ he is talking about himself”.

María José Herrera, July 2021